It was a sweltering morning in Saigon, 33°C with a heavy chance of rainfall.

Steam sprayed steadily from shop awnings as women washed colourful buckets, pots, and pans by the side of the road before a day of street vending.

Unlike other cities in Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City, better known to locals as Saigon, offers a more metropolitan take on traditional communist uniformity. Nestled in and amongst the old colonial architecture, music, fashion, and art thrive. Asian subcultures are prominent, with Japanese hotpot restaurants lining the streets alongside K-pop stores. Still, despite the efforts of the Vietnamese Communist Party and perhaps a lingering American influence, Saigon remains heavily shaped by its history, even five decades after the end of the war.

The tarmac shimmered and groaned under the weight of the traffic. On the back of a motorbike, I rode across the city on my way to meet locals from the tattoo parlour and barber shop, VietMonster.

Arriving just after noon, I was greeted by Mike, a Munich-born Vietnamese tattoo artist working out of the upstairs studio. Wearing grey VietMonster-branded capri trousers and ice-white Nikes, he looked like he’d stepped straight out of East LA.

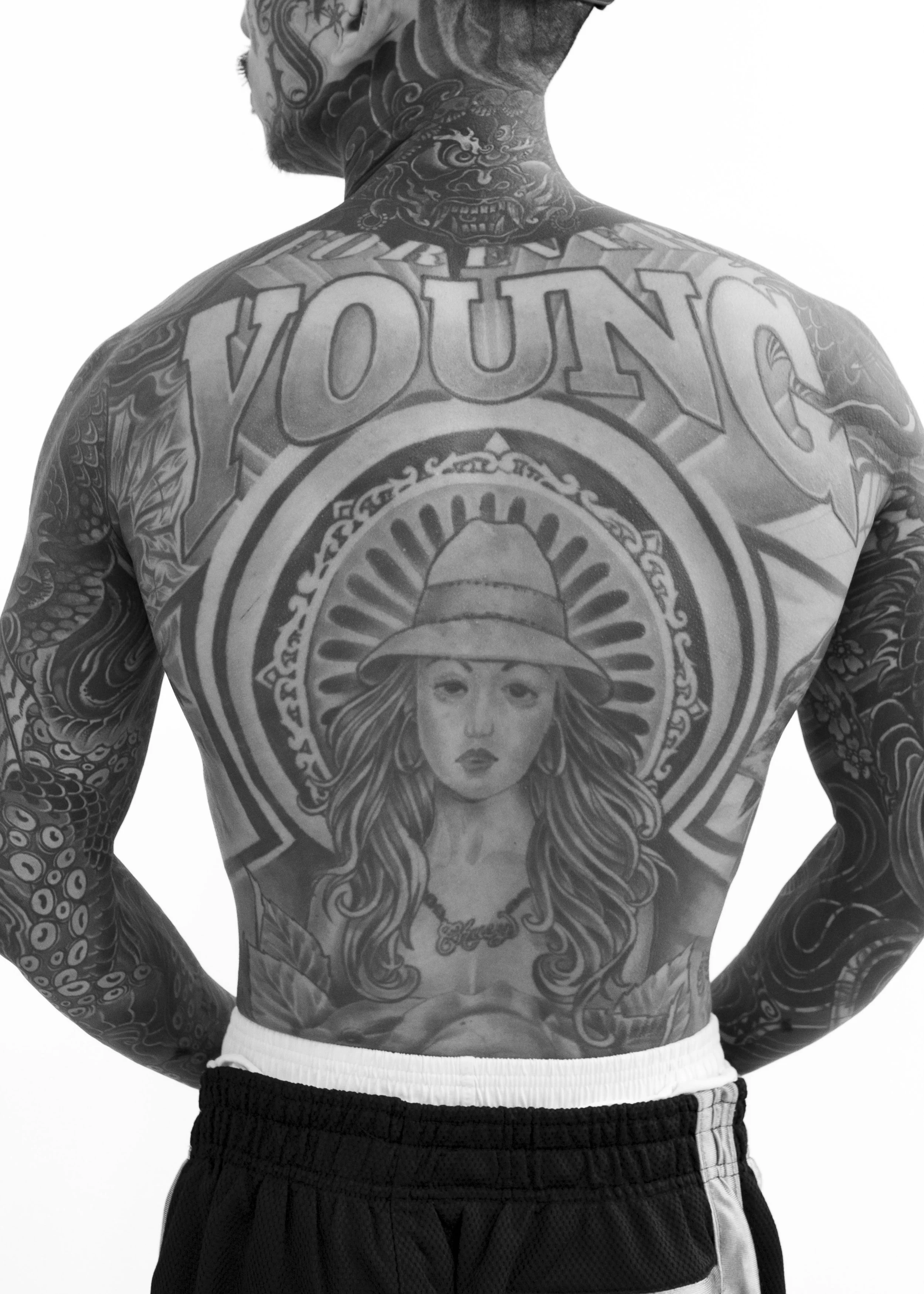

Upstairs in the tattoo parlour, I found Simba, the 65kg XL pitbull, splayed out on the floor. An artist from Compton worked away, designing a dye job on his fur. Mike introduced me to Thao, the owner and founder of VietMonster. Boasting a significant Instagram presence for his Chicano tattoos, Thao exemplifies how Vietnamese individuals are putting their mark on traditional Western subcultures.

Cholo culture originated from Mexican Americans and has roots tracing back to the 1960s. It gained widespread visibility in the 1990s, thanks to its popularity in West Coast music and culture and its adoption by groups such as N.W.A and Cypress Hill. Over the years, this distinctive style has also become synonymous with the country's gang and prison culture. However, its popularity exploded across Asia in the 1980s thanks to the importation of American lowrider magazines, transforming what was at the time considered a negative Latino stereotype into a celebration of fashion and artistry worldwide.

The VietMonster shop itself has been modelled after a California body shop. The walls of the barbershop are adorned with Chicano and Hispanic iconography. Framed photos of the shop members litter the walls, only interrupted by the occasional Madonna figure or hanging orange bandanna, a homage to the culture’s prominent Christian roots. Most notably, a fully custom lowrider sits pride of place in the shop’s centre, its “VietMonster” airbrushed hood reminiscent of Mister Cartoon’s iconic graffiti style, a style crucial when examining the history of Chicano culture in Los Angeles. Each barber and VietMonster member sports a distinctive Chicano look: long shorts or khaki chinos, high socks, and plenty of tattoos.

When I spoke to the crew, they explained they’d just returned from a Harley-Davidson convention in Vietnam. In a strange full-circle moment, the iconic American motorbike brand, perhaps once idolised in South Vietnam as a symbol of the American dream, has again become a staple of Americana fashion and motorbike culture.

When asked about visiting America, they replied that they’d never been. I was initially confused, but they explained that they were simply fans of the style, culture, and message of family they believed Chicano culture represented. Southeast Asia is no stranger to subculture mania. Countries like Japan and Malaysia have a long history of adopting, reshaping, and re-exporting their own versions of Western cultures, whether that's Emo culture in Tokyo or skinhead scenes in Kuala Lumpur.

Due to the world's technological growth and rapid interconnectivity over the past ten years, apps like Instagram, Pinterest, and Tumblr have become fertile ground for micro-communities to flourish as generations become more conscious and perhaps rebellious of the outdated cultural dynamics within their own countries.

When I asked another local photographer whom I had met in Saigon what he thought about this subculture, he shrugged and replied simply, “Gangsters.” Whether he meant that literally, or that by dressing like American cholos they were emulating the gangster image, was unclear. But one thing was certain: this style was a rebellious statement in a Vietnamese society that emphasises conformity.

At the time of writing this article, it was approaching the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War and the subsequent end of American intervention in the region. While Vietnam is now reunified, it's clear to see how its post-colonial past continues to shape life long after peace has been officially declared.

To see more of the photos, check out the gallery below.